With Key Art Photographer Frank Ockenfels

Arriving at the hillside home of photographer Frank Ockenfels, I’m guided into his office, which is chock-full of mementos, artwork, and personal books bursting with inspirations. Things are rather hectic as Frank is in the middle of moving and preparing for a gallery opening featuring his personal work. Frank is a genial sort - kind, social and not one to censor himself. He exudes an inexhaustible energy, yet registers an internal calm and confidence that makes him comfortable to be around and spellbinding to listen to.

Arriving at the hillside home of photographer Frank Ockenfels, I’m guided into his office, which is chock-full of mementos, artwork, and personal books bursting with inspirations. Things are rather hectic as Frank is in the middle of moving and preparing for a gallery opening featuring his personal work. Frank is a genial sort - kind, social and not one to censor himself. He exudes an inexhaustible energy, yet registers an internal calm and confidence that makes him comfortable to be around and spellbinding to listen to.

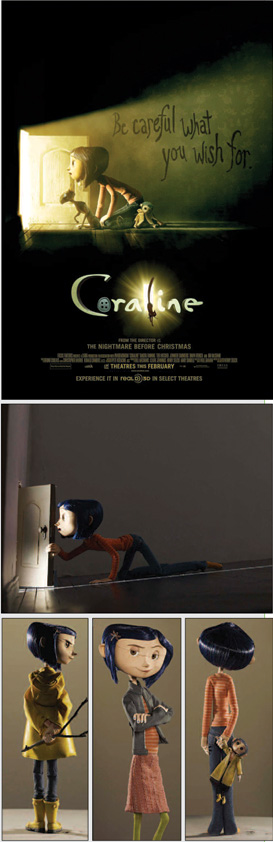

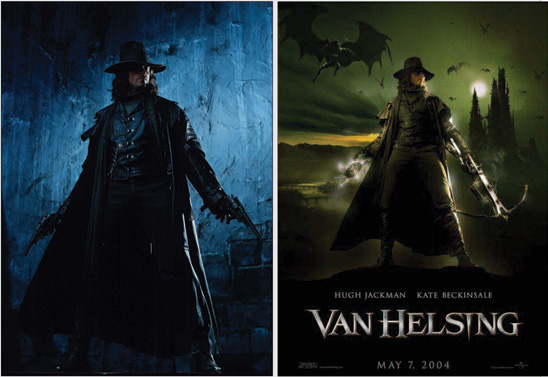

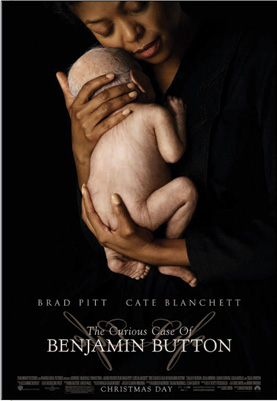

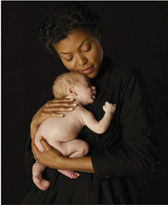

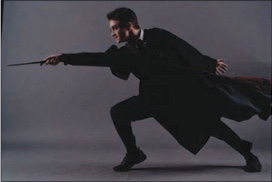

For the past 18 years his images have graced the covers of Rolling Stone, Esquire, GQ, Wired and Newsweek, in addition to hundreds of album covers, and celebrity portraits. Living in Los Angeles his specialty has naturally gravitated to entertainment photography, capturing images used in the posters for Wanted, Coraline, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, the Harry Potter films and the upcoming release of The Wolfman for Universal Pictures. The mere mention of this interview to fellow commercial photographers provokes comments of great admiration and praise. And in examining Frank’s work with a critical eye I’ve come to realize his invaluable contribution to the art of photography, which brings to mind the adage about another renowned Frank: It’s Frank’s world. We just live in it.

D – A client has just hired you. What happens next?

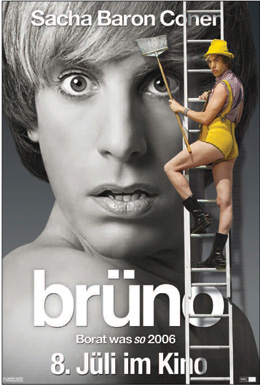

F - I’ll get a PDF or a Look Book from the designer with all their concepts, or sometimes they’ll send over the script. I’ve also had to go over to some studios and sit in rooms and read scripts. When I did Bruno, I had to go over and watch the movie to see what I’m walking into, so I have a really good sense of it. Each person seems to have a different process, but in general I’ll get a PDF of all the drawings showing how he or she wants to approach it. Then I’ll talk to the Art Director and we’ll discuss whether they’re coming to a studio that I’m setting up, or a studio on their (production) stages during a day off. Next, we start figuring out whether we needs props, how many setups we want to do, how much time do we have with each actor - all the details in how we’re going to get it done.

D - Do you prefer shooting in studio or on set?

F - I like being on set, to be honest. I know it’s a pain in the ass a lot of times for people, but - for example, we just did Jonah Hex out in New Orleans and I think if we had actually done that movie in a studio here (Los Angeles) the energy would have been completely different because they’ve already walked away from the movie. On set, they’re in the middle of being that character, and it’s important because they feed off that. A lot of times when we’ve shot in a studio, people have cut their hair, gained weight, or something’s changed about them, and they’re struggling to go back and figure out who that character is depending on how intense the movie is. Van Helsing was done on set, all the Harry Potters have been done on set, Riddick was done on set.

D - Is it disruptive to work on set with all that’s going on with the cast and crew?

F - Usually I don’t get that. I get the day off. Which is not always a good thing because if they’ve been going for 18-hour days, I’m requiring hair, make-up, everybody to come in on a day off. The whole crew walks in exhausted, and you get this kind of odd animosity because you’ve messed up the one day off they’ve had in a long time. But a lot of times when people get there, they see the images and get excited by their part in something that they really like.

F - Usually I don’t get that. I get the day off. Which is not always a good thing because if they’ve been going for 18-hour days, I’m requiring hair, make-up, everybody to come in on a day off. The whole crew walks in exhausted, and you get this kind of odd animosity because you’ve messed up the one day off they’ve had in a long time. But a lot of times when people get there, they see the images and get excited by their part in something that they really like.

D – Are there instances where you have to just show up cold on the set?

D – Are there instances where you have to just show up cold on the set?

F - I have shown up in the morning and shot in the afternoon. I have my system down of what I need to do and can quickly get my crew ready; however, we can only tweak lights or rough it up to a certain point. Like if I’m shooting my male assistant as a stand-in for Megan Fox - there’s only so far you can take that setup before you stick her in front of it, and then you can kind of tweak it and figure what works for her. Everyone’s face is different. If my assistant’s got deep-set eyes and then I go to shoot her, I may find out the light’s too much or maybe I need the light to come under more because she has eyes that need little bit more of this or that.

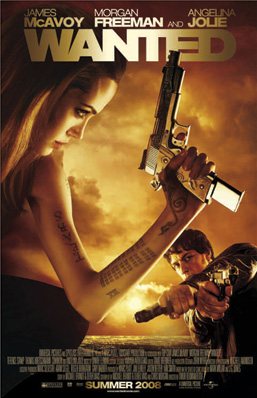

On the sly, you have to be able to quickly change everything out. This happened with the Wanted poster. We went to set and they were basically building a set behind us and we were sitting there waiting for Angelina to come in. And when she arrived, she came in with valid concerns, in the sense that she didn’t want it to look like other action movies she had done. What could we do that’s not Tomb Raider? And she started throwing ideas out on what we can do, and we lit something that’s completely in the opposite direction. She wants to be holding a gun and wants to be on the ground with the gun close to her face. We want the gun to glow but not her (to glow). Suddenly, we went from having a completely pre-lit set that took an hour to set up, and we re-lit it in a totally different direction in 20 minutes.

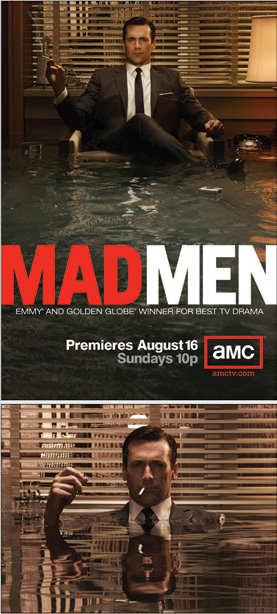

D - For the most part Posters, or Key Art, as we refer to it, is a composite of different images. Yet the Mad Men poster you shot with actor Jon Hamm sitting in a chair submerged in water was one shot - a complete concept. Is that the exception to the rule when it comes to Key Art?

F - Matt Weiner (Mad Men creator) wanted one shot. He didn’t want it to be a composite where we shoot Jon Ham, then shoot water and put it together. Now, you also need to have someone willing to do it, and Jon is a true gentleman. He sat in the water for three hours and didn’t move. He talked to us and joked around and, I have to say that at one point I handed him the camera and he was shooting us, because he was in-between shots. We’d be putting more water in and he’d just sit there, change cigarettes out, focus on what he needed to do, and didn’t complain.

F - Matt Weiner (Mad Men creator) wanted one shot. He didn’t want it to be a composite where we shoot Jon Ham, then shoot water and put it together. Now, you also need to have someone willing to do it, and Jon is a true gentleman. He sat in the water for three hours and didn’t move. He talked to us and joked around and, I have to say that at one point I handed him the camera and he was shooting us, because he was in-between shots. We’d be putting more water in and he’d just sit there, change cigarettes out, focus on what he needed to do, and didn’t complain.

More people send me emails saying, “Did you see this? This guy thinks you totally composited the whole thing.” There are only two things that changed; the Lucky Cigarette pack was like a boat on a rough ocean because of the constantly circulating water. The cigarettes kept floating out of frame and we kept pushing it back in. When it came time to figure out the shot, they pulled the one of Jon they loved, and then they put the cigarette pack where they wanted on the water. And there’s the cigarette smoke they put in. But that was it. It’s a pretty clean shot.

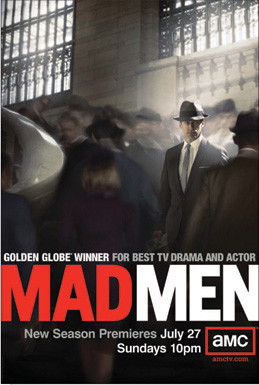

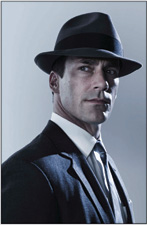

D – Tell me about the shot of Jon in Grand Central Terminal.

D – Tell me about the shot of Jon in Grand Central Terminal.

F - That is a huge composite. We knew we couldn’t shoot in Grand Central. You can’t just take over the staircase; they won’t let you do it. We spent two days in Manhattan at Grand Central shooting different angles, and from these shots we knew what we needed to do once we were back in LA in a studio.  Our set designer, Peter Gargaliano built a steel-deck staircase. I grabbed the camera, took the image and we overlaid the image and dropped it down to line up perfectly with the staircase in Grand Central. We brought in extras from the show and shot them on the stairs with a low shutter speed to blur them. And then Jon came in and we did a whole series of Jon, with light coming from behind him or different places on the staircase.

Our set designer, Peter Gargaliano built a steel-deck staircase. I grabbed the camera, took the image and we overlaid the image and dropped it down to line up perfectly with the staircase in Grand Central. We brought in extras from the show and shot them on the stairs with a low shutter speed to blur them. And then Jon came in and we did a whole series of Jon, with light coming from behind him or different places on the staircase.

D - It’s a gorgeous shot. It’s filled with atmosphere and has an aesthetic grace to it. That’s something I see in your work that I really enjoy.

F – There are Art Directors who have said to me that some (photographers) just show up with the attitude that the Art Director’s going to fix everything (in post). They don’t talk about lighting or offer much in the way of ideas.

I’ve learned about the subtleties and I think it’s important. For example, you can’t give a client black in a photo. When we shot Hellboy II, I knew it was going to skew dark, but if someone down the road says “No, we need it to be more like this,” there’s no way to pull it back (bring out detail). So it’s giving someone enough of the subtleties so the shot still has great personality and a wonderful point of light. They can then choose to go a little darker or a little lighter without losing detail.

And you may do a dark shot like that just to have one, to show, “This is where we’re going with it.” These are lessons learned when you’re younger, realizing that more than one person’s going to work on this. I remember doing a shoot once and someone actually called me up and said “Hey! Why’d you shoot this way?” I said, “That’s what the Art Director asked me to do,” and he goes, “Yeah, but he’s gone now, and I’m working on it and I can’t use this.” And I’m thinking “Huh?” Just Like Scooby Doo, going “Huh? What’s going on?” So I learned my lesson, but found my legs in learning to say: I can give you this, this, or this.

You know, I became a photographer because I love light. I love looking at how light is made. How certain skins can use this light or that. So I learned to ask questions, like: What do you want out of the light? What do you want it to feel like? Do you want the skin to have kind of a snap? Do you want it to be soft with the back being a little bit hard? Do you want the edge to be bright? Do you want it to fall off down the body? Do you want the face lit more than the hands? Light doesn’t have one dimension. It doesn’t just come at you flat. There is always something that breaks it up. So, do you want me to do that for you?

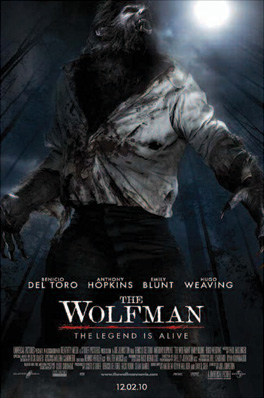

This is all stuff we did in The WolfMan. You know (refers to poster), this is Benicio Del Toro in the mask. Rick Baker did the makeup, and the hair was so life-like that you couldn’t see the seams. It was so thick and dark that I had to figure out how to get light in there. We had to do it quickly because we’re already in the middle of doing it, and it was important because we wanted it to feel like the old posters, which I think we achieved.

D- Do you have the freedom to follow your own inspiration on set?

D- Do you have the freedom to follow your own inspiration on set?

F - I like collaboration. I like working with Art Directors, saying, “This is what I’m thinking.” The collaboration of what we do is so enjoyable to me as a photographer because my job is pretty simple; I’m here to solve your problem. We have a project together and you and I are coming up with ideas and we’re listening to each other. All of a sudden something comes out of that. It’s really enjoyable to face it as a group of people creating something.

D – It’s a social experience.

F – It’s a one-of-a-kind because we all chose to walk forward together at the same time.

D – And yet sometimes it can be downright difficult. Outside of lighting a set and hitting the shutter button, good communication skills are essential, especially when connecting with an actor you’ve just met for the first time on set. How do you personally handle this awkward phase?

F – The biggest downfall of this industry is ego. And even in the case where there’s no ego involved, you have to understand that we are all just working for a point. The actor is there to be photographed as the character and I’m there to capture them for the advertiser. The minute there becomes a hierarchy on the set, or if the actor gives you that aren’t you just lucky to be in front of me kind-of-thing, the collaboration’s gone. The actor’s the key part. If he doesn’t come to play or help you out, then the rest of us struggle.

For me, I like to keep a sense of humor about everything. I’m very laid-back and people often remark that I make the process painless for them, which I take as a great compliment. I try to keep things moving. I don’t waste time doing things that are unnecessary. And, you know, it’s important to be aware of the actor. I can see when people stop, which is important to know as a photographer. When someone is done doing something and you force them beyond that, then problems begin. So I change it up. I’ll talk with them and find out what they’re interested in doing. They’ll throw out some ideas and I’ll go, “Great, let’s do that!” If you get them personally involved they’re not standing there feeling like a prop, and once again we have collaboration.

D – Who are some actors that were terrific collaborators?

D – Who are some actors that were terrific collaborators?

F – Ben Stiller is amazing. If he gave you only 10 minutes on set, it will be like most people giving you an hour because he will go through every single thing without hesitation. He reminds me of David Bowie. David can give you 10 minutes and it’s the best 10 minutes of your life. He gets very involved wanting to know why you would or wouldn’t do something. Will Ferrell’s amazing because he’s very cathartic. He’s not the type who walks around cracking jokes 24-7. But he has this ability to just turn it on. Suddenly, he’s there. He’s become the character and you watch him morph into this whole thing that comes out of nowhere. He’s very attuned to what that character will or won’t do. And Malkovich is terrific. He’s got so much going with his eyes; you really get sucked right into him.

Those are things actors ought to do. Nowadays, I think a lot of actors put the whole thing off. A lot of them won’t do special shoots. They’re renown for not doing them because they don’t see any reason to or they’re uncomfortable with it. Actors deal with millions of frames, they don’t deal with 1 frame, and sometimes they get a little deer in the headlights when you’re standing there asking them to look at you. But you have to appreciate their end of the world too. You can’t have the arrogant point of view that they’re acting like jerks. You haven’t been on the set with them for the last 3 months. You don’t know what’s been going on or how they’ve been treated.

Those are things actors ought to do. Nowadays, I think a lot of actors put the whole thing off. A lot of them won’t do special shoots. They’re renown for not doing them because they don’t see any reason to or they’re uncomfortable with it. Actors deal with millions of frames, they don’t deal with 1 frame, and sometimes they get a little deer in the headlights when you’re standing there asking them to look at you. But you have to appreciate their end of the world too. You can’t have the arrogant point of view that they’re acting like jerks. You haven’t been on the set with them for the last 3 months. You don’t know what’s been going on or how they’ve been treated.

My favorite one ever is the Bruce Willis conversation. I’ve only shot him once, and he’s a tremendous gentleman,  but on the day of our shoot I could see he wasn’t happy. We were shooting at a bar in downtown LA, and he walked up and asked who’s the photographer? And I go, “I am,” and he said, “Come here.” So we step aside, he leans toward me, smiles, and goes, “What’s about to happen has nothing to do with you.”

but on the day of our shoot I could see he wasn’t happy. We were shooting at a bar in downtown LA, and he walked up and asked who’s the photographer? And I go, “I am,” and he said, “Come here.” So we step aside, he leans toward me, smiles, and goes, “What’s about to happen has nothing to do with you.”

I said, “Okay,” then stepped back and everyone started saying, “Have him do this. Have him do that.” And he’s just standing there looking at me. He’s not moving. So I say, “Can you do this?” He doesn’t move. “Can you try this?” Bruce doesn’t budge. Oh my God, I don’t know what happened on the set. I don’t know what went down, but what a gentleman that he stepped forward and said, “Just so you know, don’t take it personally,” which I never do. I mean you can crap all over me on set. You know - who am I? They don’t know anything about me. I’m just a photographer who’s been sent in.

D - Do you ever get a job and just think; what the heck am I doing here? How am I going to light this?

F - I think in every job we have that moment. I try to re-invent myself once a year. I try to figure out something different than I’m doing, something new, a new piece of light, and a new approach to an old idea. A few years ago when I was shooting a lot of Canon stuff, I was taking screwdrivers to old plastic  lenses to see what effect I could get out of them. It’s probably why it’s always been hard for me to be sponsored by a camera company because I’ll be happy to break their lenses to make something work for me. My enjoyment in being a photographer is that I can do so many different things.

lenses to see what effect I could get out of them. It’s probably why it’s always been hard for me to be sponsored by a camera company because I’ll be happy to break their lenses to make something work for me. My enjoyment in being a photographer is that I can do so many different things.

D - I see a certain beauty in your work. Is that a primary motive for you - to find beauty in the things you shoot - even if it’s a dark piece or a horror film?

F - You know what it is? There’s honesty to it.

F - You know what it is? There’s honesty to it.

D – What does that mean?

F - How am I going to explain it to you? It’s capturing that complete synergy of the moment. Like when I worked with Angelina, she wasn’t just showing up and standing there with a gun in her hand, staring at me. We had to get to a point where she’s comfortable enough to trust me to take her picture.

It’s the arrogance with being a photographer, that I consider myself a true portrait photographer. That’s what I do. I think portraiture is a dying art to a certain extent. In a true portrait is a great conversation. There is a connection between two people and whatever is happening in that moment - those elements are what our moment is right now. An hour from now, ten minutes from now it’s a totally different picture. To have that in a photograph, to be able to create that and have that moment is what I’m always trying to do. So in trying to take a beautiful photograph, which may be dark and disgusting with a gun pointed at your face, there still has to be a certain sense of something beautiful to make you stop and look at it - that’s enticed you to say, What am I looking at? And for me – it’s honesty.

D – What’s your take on this new technology that’s adding motion to printed posters? They’re calling them Living One-Sheets and they’re popping up in all the malls.

F - It’s the conversation right now. It’s almost a Lazy-Man’s poster, and I hate to say it, but more power to the technology if people are trying to figure out ways to grab attention. But if there are hundreds of them out there, are you really going to stop and look at it? No, its just going to be mind numbing and everyone’s going to see that, right? On the other hand you don’t want to pooh-pooh it because it could be the next wave, and here you are saying, Well I think its crap, I’m never going to do that. I found myself doing that with digital, because I was the Anti-Christ, saying, I’m never going to touch digital and digital is bullshit. And now I totally love it. It’s allowed me to grow as a photographer. So I can’t dismiss it, but I question it because it’s movie poster art.

Wouldn’t it be sad to see movie posters go away? One-sheets are so beautiful when they are done. Even the worst one-sheets still make you stop and look at them. I just love movie posters. It was never a fantasy as a kid to get into them, but once I did, I got addicted to shooting them, and I have to say that it is truly my favorite thing to shoot.